The early history of writing instrument manufacture in America is still a wide open field. Though a few dedicated collector-researchers have compiled lists of the first makers and their patents, we have little detailed information about the key figures of the era. Most died before the advent of the modern biographical obituary, their passings marked only by terse newspaper death notices. Where later mentions are found -- typically in obituaries of former apprentices and employees -- details are notably lacking, and often unreliable.

Thomas Addison was the most important and successful early American pencil-case (mechanical pencil) manufacturer. His patent 736, issued May 10, 1838, is one of the earliest US mechanical pencil patents, and he became prosperous enough to earn an entry in the 1845 edition of Moses Yale Beach's

Wealth and Biography of the Wealthy Citizens of New York City ( p. 3; the same entry appears on p. 2 of the 1846 edition, while Addison is absent from the 1842 edition):

Addison Thomas .... [$]150,000

A distinguished pencil-case maker; a pioneer in this, and made his money by industry. The present ever-pointed pencil-case was first made by him, and owes its form to his ingenuity.

Addison's estimated worth has increased to $200,000 in the 1855 edition ( p. 3), and more details are given:

Addison, Thomas . . . . [$]200,000

Originally of the firm of Wilmarth and Addison, ever pointed pencil makers. They manufactured the ever-pointed pencils which were invented in England by G. Mordan, who held the patent right for the invention, dated May, 1825. After separating from this partnership he carried on a successful trade for many years, became wealthy, and is now retired from business.

It is a long jump from there to a contemporary biographical entry (

History of Bergen and Passaic Counties, New Jersey, 1882, p. 255) for John Mabie (1819-1892), which states that he spent 8 years and four months as "an apprentice in the manufacture of gold-pencil cases with Thomas Addison, the first man to engage in that business in this country", starting at the age of 12 -- thus between Jun 19, 1831 and Jun 18, 1832. Addison may have been a founding father of American pencil-case and pen-case (portable dip pen) manufacture, but any further information about his life and career we will now have to dig out from contemporary records and notices. What follows is necessarily but a first step -- to be amended and amplified as more records are found.

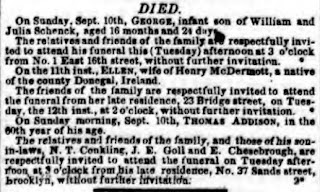

Thomas Addison died on September 10, 1854 -- too late for the compilers of Beach's

Wealth and Biography of 1855 to take notice, apparently. Brief death notices appeared in various New York City newspapers (

Evening Post, September 11, 1854, p. 3, col. 7;

Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer, September 12, 1854, p. 3, col. 7, shown below):

These notices tell us little, but in combination with census and burial records, they enable us to confirm that this was the same Thomas Addison who now lies under a rather prominent monument at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York (described and illustrated here). The inscription on that monument places Thomas Addison's birth on April 13, 1795. Other inscriptions help fill out our picture of his family, to which we will return later.

The US Census of 1850 (roll: M432_44; page: 468A; image: 619) records Addison's birthplace as Connecticut, but this may not be trustworthy. Addison was living in Middletown, Connecticut at the time, and it seems the census taker was not overly careful about ascertaining place of birth: all but one of Addison's children are also listed as Connecticut-born, even though most if not all had been born when Addison was living in New York, while the other one is mistakenly listed as being born in Ireland, appearing immediately above the two young Irish women, 17 and 20, who must have been family domestics. The oldest record of Addison that I have located to date finds him in New York City, in

Mercein's City Directory, dated June 1, 1820 ( p. 107): "Addison ---- ["Thomas" is the name above], 37 Lombardy". Addison does not appear in Longworth's New York City directories for 1808-09 or 1815-16, and I have not been yet able to consult directories from between 1816 and 1820. In Longworth's directory for 1822-23 ( p. 53), he is listed as "Addison Thomas, jeweller 84 Prince". Addison is first listed as a pencil case maker in the next edition, for 1823-24 ( p. 53), as shown below:

Longworth's listings do not change until the issue for 1826-27 ( p. 54), which reads "Addison & Co. Thomas, jewellers 68 Spring h. 84 Prince". The partnership was already established by September 15, 1825, as an advertisement appears in the

New York Evening Post of that date ( p. 4, col. 1) offering two structures to let, a two-story brick building in the rear of 146 Washington, and a wooden shop in the rear of 84 Prince, applications to be made to Thomas Addison & Co., 68 Spring (an advertisement for "Adison's patent self-pointed pencil cases" appears in the same issue, p. 8, col. 5). An APPRENTICES WANTED ad in the December 3, 1825 issue of the same paper ( p. 1, col. 6) reads, "Two apprentices to the Jewellery business wanted immediately by the subscribers, about the age of fourteen or fifteen years. Apply at No. 68 Spring street. THOMAS ADDISON & CO."

Listings for Thomas Addison & Co. at 68 Spring Street continue through three annual issues of Longworth's directory, though Addison's home address changes from 84 Prince to 104 Spring to 422 Broome. In the directory for 1830-31, however, Thomas Addison & Co. is no more, and the listing ( p. 92) is simply "Addison Thoams [

sic] jeweller & pencil-case-maker 157 Broadway

up stairs h. 422 Broome".

The notice reproduced above (from the

New York Evening Post of September 7, 1829, p. 3, col. 2.) dates the dissolution of Thomas Addison & Co. to August 1, 1829, with the statement that "The subscribers will continue the manufactory of Jewelry and Pencil Cases. . . under the firm of WILLMARTH [sic], MOFFAT & CURTIS." Wilmarth, Moffat & Curtis continues to be listed in

Longworth's at 68 Spring Street up until the 1834-35 edition ( p. 743), the above notice suggesting no further involvement by Addison with his former partners. The Wilmarth of Wilmarth, Moffat & Curtis was Jonathan Wilmarth, whose death on September 26, 1835 at the age of 41 (

New York Evening Post, Oct 10, 1835, p. 7, col. 2) would have necessitated the dissolution of the firm (partner John L. Moffat would later join the Gold Rush, finding lasting numismatic fame as the premier maker of California gold coins).

Addison appears to have found new partners, setting up as Addison & Co. A couple of years later, the notice below (

New York Daily Advertiser, May 4, 1831, p. 3, col. 5) was published, announcing a change in partners with the replacement of Jacob I. Lowns by Henry Withers as of March 31, 1831, with no change to the business name. The address is noteworthy: 157 Broadway would become Waterman's headquarters some 60 years later. As it is the address listed for Thomas Addison in the 1830-31

Longworth's, the business was likely first established there in late 1829. Addison did not stay there long, however. In the 1831-32

Longworth's (p. 93), his business address is 1 Cortlandt, and in the 1832-33 and 1833-34 editions, 4 Green (his home address stays as 422 Broome from the 1829-30 to the 1839-40 editions).

By the time the 1833-34

Longworth's ( p. 89) was compiled, Addison & Co. had become Addison, Wilmarth & Co. The relationship between this partnership and Wilmarth, Moffat & Curtis is unclear, with two different Curtises and Wilmarths involved (Henry and Joseph Curtis, William M. and Jonathan Wilmarth). As noted above, Wilmarth, Moffat & Curtis is listed at 68 Spring Street until the 1834-35

Longworth's, in which Addison, Wilmarth & Co. takes over that address. Wilmarth, Moffat & Curtis is now listed as "jewellers 13 John", but disappears from city directories the year after. Thomas Addison continues to be listed as a pencil case maker at 68 Spring in city directories up through the

Doggett's for 1845-46 ( p. 15), then disappears. The partnership of Addison, Wilmarth & Co. last appears in the

Doggett's for 1842-43 ( p. 11), though William M. Wilmarth continues to be listed at 68 Spring for one more edition ( p. 369), after which his previous home address, 49 Crosby, is given instead.

If Addison retired around 1845, he would have been fifty. He had been a property owner for some time, as various newspaper advertisements indicate. In the February 7, 1834

Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer, for example, he offers two two-story brick houses to let at the the southeast corner of Spring and Crosby ( p. 4, col. 1), and in the March 18, 1844 edition we see ( p. 4, col. 1):

TO LET - The large room about forty feet square,

containing 18 or 20 windows in the third story of the build-

ing, No. 68 Spring street, lately occupied for a school . . .

or any manufacturing . . . where light is required.

On the premises of THOMAS ADDISON.

Addison was also involved in multiple professional organizations; in the July 15, 1835

Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer there is a report of a meeting of the Gold and Silversmiths' Temperance Society ( p. 2, col. 4) in which Addison is mentioned as a manager, teller, and active participant. He was on the Board of Directors of the Mechanics Institute for the 1836-7 term, serving on the Committee of Finance. And in 1839, his name is listed as a reference in an advertisement for a "Juvenile Boarding School" ( col. 4), while the following ran in the

New York Tribune of April 19, 1842 ( p. 3, col. 1):

Gold and Silver Artizans, Attention!

-The Gold and Silver Artizans of this City and vicinity,

opposed to the efforts now being made by the Importers and

others interested in Foreign Manufacture to reduce the du-

ties on Jewelry, Silver-Ware, &c., are requested to meet at

the Marion House, 165 West Broadway, on Wednesday, the

26th inst., at 8 o'clock, P. M., to sign a remonstrance against

this measure, which is so prejudicial to the Revenue of the

Country and to our interests, and to transact other impor-

tant business. By order of the Executive Committee,

THOMAS ADDISON, Chairman.

There is also a mention of Addison in the

New York Daily Tribune of Dec 7, 1844 ( p. 1, col. 6) as one of seven directors of the Mechanics' Banking Association recently re-elected, and another on December 6, 1851 ( p. 2, col. 5) as one of three members of the Committee for Subscriptions for stock in the New York and Boston Railroad. Perhaps these ventures proved just as lucrative as pencil manufacture, given that Beach's

Wealth and Biography of the Wealthy Citizens of New York City (cited above) had Addison's assets increasing by a third between 1845 and 1855.

Addison's last residence was at 37 Sands Street, Brooklyn. He is first listed there in

Hearnes' Brooklyn City Directory for 1853-1854, p. 19. It had previously been occupied by John Bell Graham, who died there on March 11, 1853. The site is now dominated by the approach ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge, but this advertisement from the

Brooklyn Eagle, placed shortly after Addison's death, gives us some idea of what the house looked like (March 1, 1855, p. 4, col. 1):

TO LET -- A Three Story Brick House, No.

37 Sands street, to a private family ONLY - has gas,

range, bath rooms, &c, &c. - Apply to

JAMES A. H. BELL,

No 149 Maiden Lane, New York

Feb. 3, 1855.

Addison's estate also included stocks, as is indicated by an announcement of an executor's sale in the

New York Morning Courier of March 27, 1855 ( p. 1, col. 5). Settlement of the estate continued into spring, with a notice for any claimants to come forward appearing in the

New-York Daily Times, May 4, 1855, col. 6.

For the last several years in which he appears in New York City business directories, Addison's home address was 79 Spring Street. But where was he living between his apparent retirement around 1845, and his move to Brooklyn in 1853? The 1850 US Census found Addison living in Middletown, Connecticut, along with his wife, Betsey, and six children: Thomas, 18; Samuel, 16; Joseph, 15; Betsey, 13; Reuben, 10; and Abraham, 9. The household help included two young Irish women and a 40-year-old laborer; 40-year-old Angeline Brownson, however, was more likely a widowed sister or sister-in-law. The Census records for 1830 and 1840 are less detailed; the family was then living in Ward 14 of New York City, consistent with the evidence of the directories.

The most detailed information on the Addison family I have been able to find has been through the inscriptions in the family vault and burial records as posted here, here, and here. It seems some inscriptions are quite worn, which may account for dates inconsistent with those of the Census:

Thomas Addison, d. Sep 10, 1854, aged 59 years 4 months and 28 days (thus b. Apr 13, 1795)

Two wives, who were sisters (their father Reuben Curtis, 1757-1816):

Silence (Sally) White Curtis d. Dec 5, 1828, 31 yrs, 8 mo. 24 days (thus b. Mar 11, 1797)

Betsey Curtis Addison (Oct 20, 1799 - Aug 27, 1873)

Children: Cordelia Eugenie Addison (Feb 5, 1826 - Mar 20th 1837, Aged 11 years 1 mos 15 days)

Martha Isabella Addison (Aug 10, 1824 - Dec 8, 1841, 17y 3m 28dy)

Anna Louisa Addison Chesebrough (Feb 20, 1823 - Oct 4, 1845, 22y 7m 14dy)

Reuben Benjamin Addison (Jul 8, 1843 - Oct 11, 1854, 11y 3m 3dy) but b. 1840 per 1850 census

Samuel D. Addison (c. 1834 - Jul 1862)

Joseph Addison (c. 1835 - Feb 1861)

Thomas Addison Jr (Apr 18, 1835 - Feb 22, 1857, 21y 10m 4dy) but b. 1832 per 1850 census

Adriana Augusta Addison (after 1850? - Jan 7, 185?, 2y 8m 9dy)

Betsey Curtis Addison (Apr 3, 1837 - Oct 22, 1853, 16y 6m 19dy)

Note that many of the family members were originally buried at the New York City Marble Cemetery at 52-74 East 2nd Street, between Second and First Avenues ( Vault 26, Thomas Addison and Others)

and were reinterred at Green-Wood in Brooklyn on December 14 and 16, 1854.

I have not traced any living descendants, but there are surely a good number through Addison's daughter Anna Louisa, whose daughter Anna Louisa Chesebrough had no less than eleven children with John James Ingalls. Through reference to other family search sites, it seems likely that Thomas Addison was born in Newton, Connecticut.